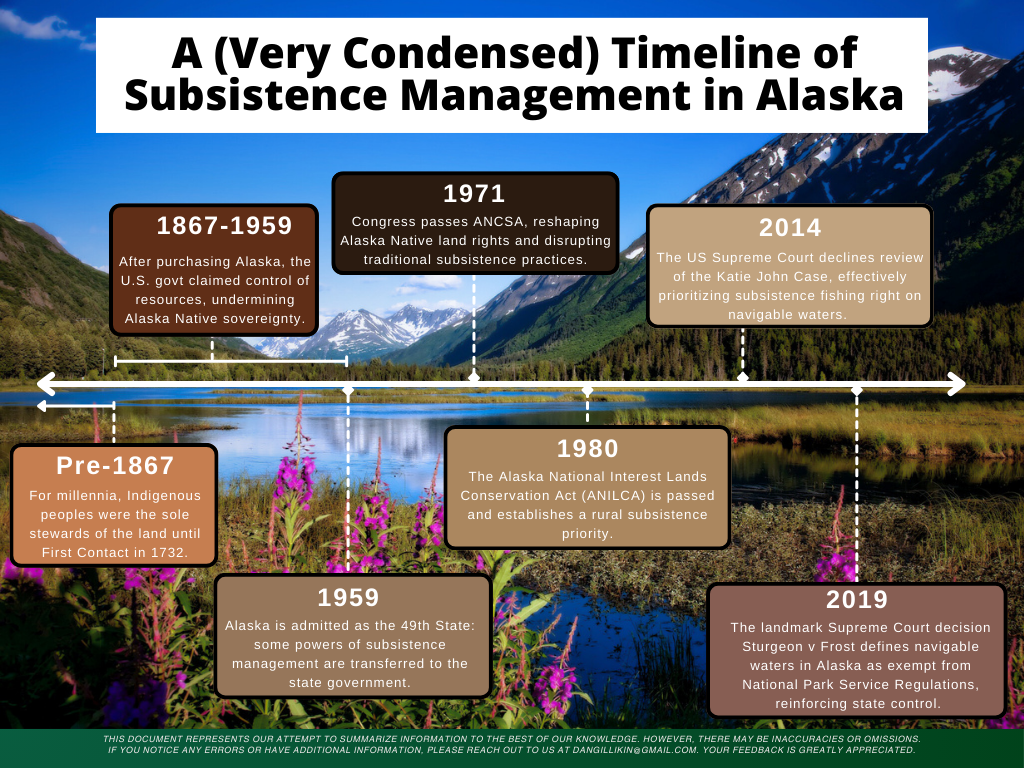

Chronology of Subsistence Management in Alaska

Disclaimer: This document represents our attempt to summarize information to the best of our knowledge. However, there may be inaccuracies or omissions. If you notice any errors or have additional information, please reach out to us at dangillikin[at]gmail.com. Your feedback is greatly appreciated.

Summary: For thousands of years, Indigenous people have lived in Alaska and engaged in a subsistence way of life. Following colonization and Alaskan statehood, subsistence management can be characterized by a series of disagreements between the state and federal government beginning after statehood and continuing to the present day, outlined through multiple lawsuits settled by the landmark court decisions. The federal government managed all of Alaska’s natural resources from the acquisition of Alaska to statehood; after Alaska gained statehood in 1959, land and water jurisdictions switched hands and have been reinterpreted multiple times by the courts (ex., Katie John) and new legislation (ex., ANCSA). At the heart of the issue is the right of Alaska Native people to engage in subsistence activities in the management of subsistence resources. McDowell v State (1989) and other cases have resulted in a dual management system for subsistence in Alaska, due to a conflict between federal legislation (ANILCA) establishing subsistence priority for rural Alaskans, in contrast to the Alaska Constitution’s equal protection clause which does not allow for a rural priority. Today, the federal government continues to provide a priority use for federally qualified subsistence users. In conclusion, subsistence management has never been and is not a settled question of authority and will likely continue to evolve according to native, state, and federal needs in the coming decades. As resources diminish, food security and traditional ways of living are continually under threat, making the need for native representation greater now than at any time.

Pre-1867

For thousands of years, Alaska Natives harvest fish and wildlife resources. Indigenous peoples actively managed their terrestrial and marine resources and ecosystems.

1867-1959

Following the Alaska Purchase, the Federal government manages Alaska’s fish and wildlife resources. Prior to statehood, the federal government controlled Alaska’s natural resources and management thereof.

1960

The Federal government transfers the authority to manage fish and wildlife in Alaska to the new State government.

1971

Congress passes the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act, (ANCSA) which conveys to Alaska Natives title to more than 40 million acres of land and nearly $1 billion in compensation. ANCSA also extinguishes aboriginal hunting and fishing rights. The Conference Committee report expresses the expectation that the Secretary of the Interior and the State of Alaska would take the action necessary to protect the subsistence needs of Alaska Natives (§ II, III).

1978

State subsistence law (Ch. 151 SLA 1978) creates a priority for subsistence use over all other uses of fish and wildlife, but does not define subsistence users.

1980

Congress passes the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA). § 811. (a) specifically protects the subsistence needs of rural Alaskans.

1982

The Alaska Board of Fisheries and Game adopts regulations creating a rural subsistence priority (5 AAC 99.010). The state program is in compliance with ANILCA.

1988

Kenaitze Indian Tribe v Alaska challenged the “rural area” definition and won subsistence rights for their tribe.

1989

In McDowell v. State (1989) the Alaska Supreme Court ruled that the rural residency preference violates the equal access clause of the Alaska Constitution. This meant that “rural” as a qualifier for subsistence was eliminated from state definition, and as a result the state has been unable to change its regulatory framework to comply with ANILCA. And until the state does so, the federal government manages subsistence harvest on federal public lands and waters in Alaska.

In Bobby v Alaska (1989) Alaska Federal District Court had also held that neither ANILCA nor Alaska's subsistence law preclude a defendant from challenging the validity of a hunting regulation as a defense in a criminal prosecution.

1990

The Federal government begins managing subsistence hunting, trapping and fishing on Alaska’s Federal public lands. The state legislature convenes but finds no solution to maintain control of the lands under state law/authority. The federal government establishes temporary subsistence management regulations. This creates a dual management system for subsistence users in Alaska.

1991

In US v Alexander (1991) the 9th Circuit held that customary trade is in fact a subsistence use accorded a priority under ANILCA.

1992

Between 1985 and 1992, aspects of Alaska’s subsistence statutes—primarily those dealing with the definition of a subsistence user and the role of a priority for rural residents in times of shortage—were amended, such that state and federal subsistence laws became incongruent. The Federal government adopts final subsistence management regulations for Federal public lands. The federal subsistence board establishes Regional Advisory Councils for subsistence regions.

These regulations control federally qualified subsistence users: this means a rural Alaska resident qualified to harvest fish or wildlife on Federal public lands in accordance with the Federal Subsistence Management Regulations. Only individuals whose primary, permanent place of residence is in communities or areas that the Board has determined to be rural are eligible for the subsistence priority.

In State v Morry (1992) the court upholds McDowell and clarifies responsibility of the state related to subsistence.

1993

The BOF made positive findings for customary and traditional uses of all salmon species in the entire Kuskokwim Area and the Yukon Area. As part of these findings, the BOF then determined the amount reasonably necessary for subsistence (ANS) in these respective areas as one means to provide reasonable opportunities for subsistence uses.

1994

In Katie John v US (1994) a federal district court ruled that since the US holds an interest in the navigable waters of Alaska, they fall under ANILCA's definition of public lands and the Secretary of the Interior was charged with the management of subsistence fishing in the navigable waters of Alaska.

Marine Mammal Protection Act Amendments uphold native hunting exemptions for subsistence.

1995

In Alaska v Babbitt (1995)/Katie John II The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals rules that the Federal Subsistence Board’s management of subsistence fisheries includes all navigable waters in which the United States holds reserve water interests, such as waters on or next to wildlife refuges, national parks, and national forests. This limits the scope of waters defined in the original Katie John case but still upholds the inclusion of waters under the definition of public land. In Alaska v Babbitt (1995) Alaska challenged the federal government’s authority to implement the federal subsistence preference and appealed the decision of Katie John I but both state and federal courts sided with the ruling of the federal court.

In State v. Kenaitze Indian Tribe (1995) Court held that it violates the constitutional provisions in Article VIII to consider how close the fish and wildlife resource is located to where the user lives. when determining subsistence priority.

In Totemoff v. Alaska (1995) the Alaska Supreme Court rules that ANILCA does not give the federal government the power to regulate subsistence hunting and fishing in such navigable waters, and that no federal court other than SCOTUS can control the decisions of state courts, rejecting Katie John II.

1995-7

US and Canada sign protocol amending Migratory Bird Treaty to authorize indigenous uses of migratory birds and eggs, a treaty with Mexico is also amended similarly.

1996

Alaska asks the US Supreme Court to review the Katie John case to clarify the conflicting cases of John and Totemoff. The court refused and turned the matter to agencies to adopt regulations specifying control of the water. Congressional moratoriums prevent the agencies’ ruling from taking effect until October 1, 2000.

1996-8

In State of Alaska v Native Village of Venetie (1996) decision, the Ninth Circuit upheld the existence of "Indian country" as applied to tribally owned ANCSA village corporation lands; however, that decision was reversed by the U.S. Supreme Court, which held unequivocally that ANCSA lands do not satisfy the legal requirements for a "dependent Indian community" in 1998.

1998

U.S. Supreme Court rules in Alaska v. Native Village of Venetie Tribal Government that lands Native villages received under terms of ANCSA are not “Indian country,” a term used to designate areas where federal Indian laws apply. The ruling means that on ANCSA lands, Alaska Native governments do not have tax and other authority granted to tribal governments in Indian country.

1999

Federal subsistence regulations expand management to include fisheries on all Federal public lands and waters as a result of the ruling in Alaska v Babbitt.

2000

Executive Order 13175 “Consultation and Coordination with Indian Tribal Governments” to “establish regular and meaningful consultation and collaboration with tribal officials in the development of Federal policies that have tribal implications”.

2001

In John v US (2001) the dispute over the governance of the river and native subsistence fishing rights is settled by the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, who reaffirms their earlier ruling: Katie John wins the fight for a priority for subsistence fishing on navigable waters.

Alaska Governor Tony Knowles meets Katie John in person and subsequently decides not to appeal the case to the SCOTUS.

In 2001, the BOF amended these ANS ranges for both rivers using subsistence harvest data from the years 1990 to 1999.

2002

Federal Rules and Regulations established for subsistence on public lands in Alaska under ANILCA.

2005

The State of Alaska and Katie John both file opposing lawsuits challenging the federal agency’s jurisdiction over navigable waters.

2007

In State Dept. of Fish and Game v. Manning (2007) the Alaska Supreme Court struck down a game ratio cap which determined whether a community had access to alternative sources of game as an unconstitutional limitation on subsistence hunting.

2009

The US District Court of Alaska upholds the original final rule in Katie John as reasonable.

2011

The Federal Subsistence Board establishes new regulations for seasons, harvest limits, methods, and means related to taking of fish and shellfish for subsistence uses in Alaska for 2011-2013.

2012

In Alaska Fish and Wildlife Conservation Fund v. State (2012) the Alaska Supreme Court held that the subsistence statute protects a “traditional culture and a way of life.”

In Native Village of Eyak v. Blank (2012) the United States District Court for the District of Alaska rules that 5 native villages in the Chugach do not have commercial fishing rights in the Chugach due to inadequate evidence that they controlled historical fishing waters at the exclusion of other tribes. This ruling guarantees tribes in the Chugach only subsistence fishing rights, limiting tribal sovereignty.

2013

A panel of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the district court’s decisions upholding the 1999 Final Rules promulgated by the Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary of Agriculture to implement part of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act concerning subsistence fishing and hunting rights.

2014

In 2014, the US Supreme Court declines to review the Katie John case, effectively ending the case. Post-Katie John, a string of Alaska governors sue the federal government to reverse federal claims of authority over subsistence fishing in Alaska.

2015

DOI Secretaries allow the Federal Subsistence Board to define which communities or areas of Alaska are nonrural. The process enables more flexibility to account for regional differences, with more input from the Subsistence Regional Advisory Councils, Tribes, Native corporations, and the public.

2019

Sturgeon v. Frost: the Supreme Court unanimously rules that the ANILCA (a federal law) defines navigable waters in Alaska as "non-public" lands and that they are exempt from the National Park Service's national regulations. Essentially, the court says ANILCA creates exemptions for Alaska that the other states are not subject to.

2021-2

Alaska’s Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) and the Federal Subsistence Board (FSB) issue conflicting emergency orders for the Kuskokwim River. The federal government wants to limit subsistence fishing to rural residents, while ADF&G wants to keep it open to all eligible Alaskans. This conflict prompts the filings of multiple injunctions by the state of Alaska and the federal government.

2024

In United States, et al. vs State of Alaska, et al. a federal judge rules that ADF&G cannot allow all Alaskans to gillnet fish on the Kuskokwim River during federal fishing closures, ending the emergency order jurisdiction crisis. The ruling empowers the FSB to enforce rural subsistence priority granted by ANILCA.

2024

Three additional public members, nominated by federally recognized tribal governments in Alaska, are added to the Federal Subsistence Board. This addition increases native representation in federal decision-making on subsistence management.

Secretarial Order 3413 transfers the Office of Subsistence Management (OSM) from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to the Department of Interior. This transfer consolidates subsistence management in an effort to increase bureaucratic efficiency.

A Memorandum of Understanding between agencies of the federal government and native tribes and corporations establishes the Gravel to Gravel Keystone Initiative, designed to safeguard salmon in the Yukon, Kuskokwim, and Norton Sound regions as fishery closures impact native ways of living.

Acknowledgments

This document is a project of the Middle and Upper Kuskokwim Watershed Group. We would like to extend our sincere thanks to Dan Gillikin (Native Village of Napaimute), Eleanor Hohenberg and John Matuszewski (Georgetown University), and Brendan Hegarty and Barbara Johnson (Native Village of Georgetown) for their invaluable contributions to this project. Without their dedication and hard work, this document would not have been possible. Thank you for your efforts in bringing this project to fruition.